If we know one thing about The Tin Woodman of Oz, it’s that he has a heart. A heart carefully chosen by the Wizard of Oz himself. The very kindest and tenderest of hearts, so kind and so tender that the Tin Woodman even goes so far as to protect the very insects of his kingdom from physical pain. The very best of hearts—

But what if we’re wrong?

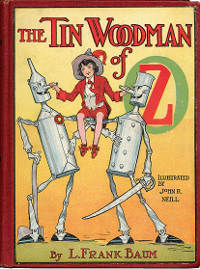

The Tin Woodman of Oz begins when Woot the Wanderer, a young boy who woke up bored one day and decided to wander around Oz for entertainment, arrives at the palace of the Tin Woodman. Fascinated by the sight of a living man molded from unliving tin, the boy asks the Tin Woodman for an explanation. The Tin Woodman obliges. He had once been an ordinary man, until he fell in love with a lovely young girl who worked for a rather less lovely witch (the Wicked Witch of the East, best known for getting crushed by Dorothy’s house). To drive him away, the witch enchanted his axe, cutting off first his legs, then his arms, then his body, and finally his head, each replaced, bit by bit, by tin. The girl remained at his side, loyally and lovingly. But alas, the now Tin Woodman found that he no longer had a heart, and without a heart, he could no longer love the girl. He set out to find one, leaving the girl behind. And even after finding one, he did not return—because, as he explains, the heart the Wizard gave him is Kind, but not Loving. Woot points out that it isn’t even very kind:

Because it was unkind of you to desert the girl who loved you, and who had been faithful and true to you when you were in trouble. Had the heart the Wizard gave you been a Kind Heart, you would have gone home and made the beautiful Munchkin girl your wife, and then brought her here to be an Empress and live in your splendid tin castle.

The Scarecrow emphatically agrees with this judgment. (As did, apparently, several children who wrote Baum eagerly wanting to know what had happened to the girl.)

Shocked by this statement—the first ever to question the Tin Woodman’s essential kindness—the tin man thinks for a moment, and then decides to find the girl, named Nimmee Amee, and bring her back to his castle. He is utterly confident that she will be delighted by his offer, if perhaps a bit angered that he has taken so long. The Scarecrow and Woot eagerly join the search, later joined by Polychrome, the Rainbow’s Daughter.

Beneath the ongoing puns (and an extremely silly encounter with balloon people), The Tin Woodman of Oz is a surprisingly serious book, dealing with issues of identity and fidelity. Throughout the book, the Tin Woodman and his companions are forced to confront assumptions about who and what they are. When they are transformed into animal shapes, for instance, the Tin Woodman receives his first clue that the tin he takes such pride in may not always be the best of materials. As a tin owl, his feathers clatter and rattle in a very un-owl like way, and he is forced to admit that he looks utterly ridiculous. It’s the first hint that tin may not be as superior to “meat” (the term the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman use for living flesh) as the Tin Woodman would like to claim.

Later, the tin hero receives another jolt when he discovers a second tin man, the Tin Soldier. He is less unique than he thought himself. Matters worse when he discovers his old head, disconnected from any other body parts, but still alive and talking. As it turns out, the old head has a disposition that is not kindly in the least. Later, his tin body gets badly dented, and he and the Tin Soldier, despite their tin, are almost unable to walk, requiring fairy aid. Tin might not be quite as durable as he has thought. And despite his confidence that the pretty Nimmee Amee will be patiently and happily awaiting his arrival—well, he has a shock there too. For once, Baum avoids the expected happy ending, instead giving a surprisingly realistic, if ironic one.

The scene where the Tin Woodman confronts his old head is decidedly creepy, to say the least, and not just because the head is not at all happy to see his former tin body. The thought of becoming a disembodied head eternally stuck in a closet with nothing to think about other than the wooden grains of the cabinet…Disturbing might be putting it mildly. The encounter has some metaphysical issues as well. The Tin Woodman admits that the head’s personality is not quite as he remembered it, but it still begs the question: how much of the Tin Woodman is the new tin man, and how much Nick Chopper, his old “meat” body? The encounter suggests that the Tin Woodman has only memories (and even those are suspect); almost nothing else of Nick Chopper is left. On one level, this is somewhat disconcerting, suggesting that personality and soul are created by appearance—in direct contrast to the themes of other books, which focus on how unimportant and deceptive appearances actually are. But on another level, Nick Chopper has not merely changed his face. He has undergone a radical transformation: he no longer eats or sleeps or drinks, and on a not so minor level, he is no longer a humble woodcutter, but the vain and wealthy Emperor of the Winkies.

Which in turn suggests some of the positive developments that can come with embracing change—and, to an extent, accepting and adjusting to disabilities. After all, the Tin Woodman, who rejoices in his crafted tin body, is considerably more content than the irritated head of Nick Chopper, who has not, it seems, asked for a second tin body which would allow him to leave the cupboard that traps him. At the same time, Baum cautions about relying too much on these changes: the Tin Woodman’s overconfidence in the quality and durability of tin is precisely what leads him into the dangers of this book.

One other major transformation: in this book, Baum embraces magical solutions to every difficulty. To escape the giant castle, the group must use a magical apron. To restore their original forms, they must depend on Ozma’s magic and enchanted powders. Polychrome uses her fairy magic to heal a boy with twenty legs and to fix the dents of the Tin Woodman and Tin Soldier. Quite a contrast to previous Oz books, where characters turned to quite ordinary things to solve problems and defeat magic.

And for once, a book not only free of Ozma fail, but a book where the girl ruler actually does something useful, for once justifying all of the endless praise and love she receives from her subjects.

The one question I still have: since birds can fly only because their feathers are so lightweight, how on earth does a comparatively heavy tin owl fly? I guess this is another question that can only be answered through magic.

Sidenote: the word “queer” did not have its current contemporary meaning when Baum wrote the book, but it’s still amusing to read how the Tin Woodman’s servants all proudly call him “queer” as they march visitors up to his private rooms—where he is happily “entertaining” his best friend and travelling companion, the Scarecrow. Not that we should probably read too much into this.

Mari Ness is now going to have nightmares about an eternal life as a head stuck in a closet. She lives in central Florida.